-

George Washington strove to be the embodiment of civilized conduct – the calm amidst the storm -- in the War of Independence. Twenty years before, a French book had accused him of being a notorious violator of the customs and usages of Enlightened warfare after his actions in the Seven Years War between Britain and France.

Credit: Left: John Trumbull, General George Washington at Trenton, 1792. Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of the Society of the Cincinnati of Connecticut. Right: Beinecke Library, Yale University.

-

Major John André’s execution for spying put on display the strange moral logic of the laws of war. This self-portrait, sketched as André awaited his death, shows the soldier as an icon of Enlightenment virtue.

Credit: John André’s self-portrait, 1780. George Dudley Seymour Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

-

![<p>When the British army burned the capitol building in Washington, D.C., in 1814, President James Madison accused them of violating the “rules of civilized warfare.”</p><p>Credit: George Munger, <em>[U.S. Capitol after burning by the British]</em>, c. 1814. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.</p> Burned Capitol](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/03_burned_capitol_02160u.jpg?itok=tBj5ZIHb)

When the British army burned the capitol building in Washington, D.C., in 1814, President James Madison accused them of violating the “rules of civilized warfare.”

Credit: George Munger, [U.S. Capitol after burning by the British], c. 1814. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

-

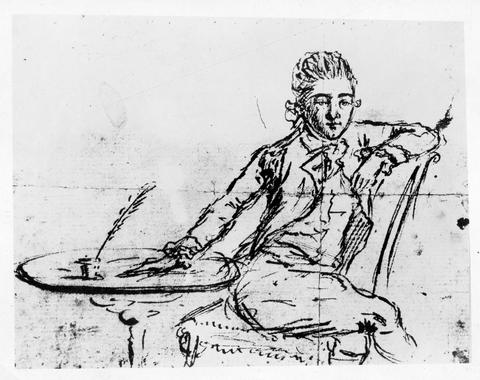

An American artist depicted British complicity in the massacre of American prisoners of war at Frenchtown along the River Raisin. Note the British camp and flag in the background at left.

Credit: Massacre of the American prisoners at French-town on the River Raisin by the Savages under the command of the British Genl. Proctor: January 23d. 1813. William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

-

From 1815 to 1828, as the U.S. minister in London, as secretary of state, and then as president, John Quincy Adams insisted that it was unlawful to carry off enemy slaves in wartime. Later in life, Adams reversed his position and predicted that slavery would end in a terrible war laying waste to the South.

Credit: C. W. Peale, John Quincy Adams, 1819. Courtesy of the Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection.

-

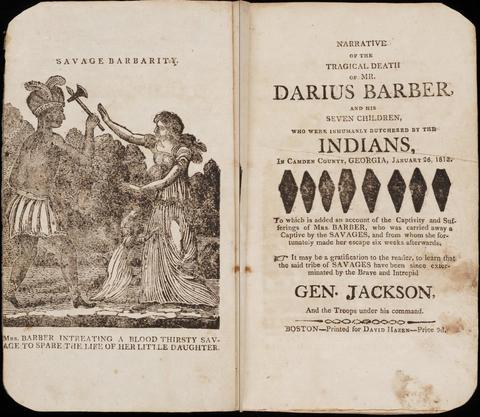

Bitter fighting among settlers and Indians along the Florida-Georgia border in 1818 helped propel future president Andrew Jackson into the Seminole War.

Credit: Savage Barbarity, from Eunice Barber, Narrative of the tragical death of Mr. Darius Barber, and his seven children, who were inhumanly butchered by the Indians (Boston: David Hazen, 1818). Courtesy of the General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

-

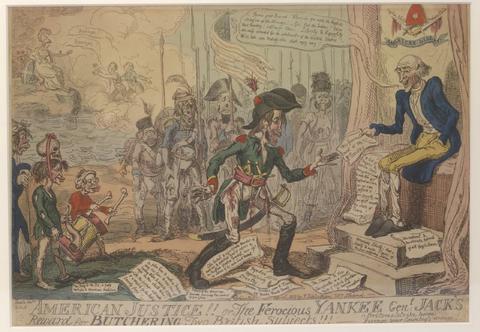

The London press viciously lampooned Jackson as a bloodthirsty butcher leading a nation of desperate savages.

Credit: George Cruikshank, “American Justice!! Or the Ferocious Yankee Genl. Jack’s Reward for Butchering Two British Subjects!!, 1819. Courtesy of the Tennessee State Museum.

-

War with the Seminoles did not come to an end until shortly before the Civil War. This rare 1836 frontispiece depicts a massacre of white settlers by Seminole Indians and escaped slaves.

Credit: Massacre of the Whites, from A True and authentic account of the Indian war in Florida (New York: Saunders & Van Welt., 1836). Courtesy of the General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

-

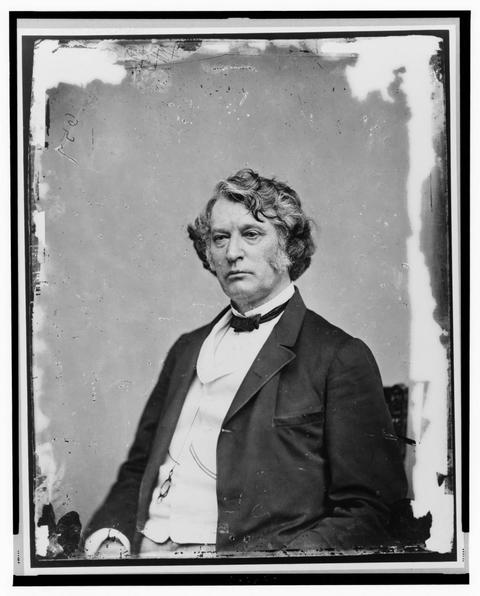

As a young man, Charles Sumner criticized the laws of war as legitimating lawless violence. By 1861, he defended a war against slavery and helped introduce Lincoln to John Quincy Adams’s late-in-life arguments about the fate of slavery in wartime.

Credit: Hon. Charles Sumner of Mass., c. 1855-1865. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

An image long thought to depict General Zachary Taylor is more likely Winfield Scott, whose Mexican War military commissions were praised by supporters and condemned by critics.

Credit: N. Currier, An available candidate--the one qualification for a Whig president, 1848. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

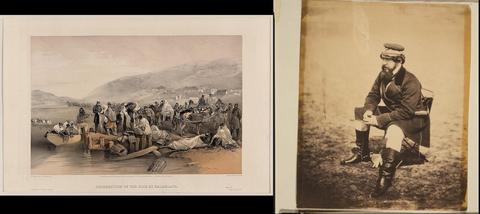

The Crimean War in 1854 helped produce new interest in Europe in humanitarian aid to the sick and wounded. It also featured the first war modern reporting in the form of journalist William Howard Russell’s dispatches from the front for the London Times.

Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

-

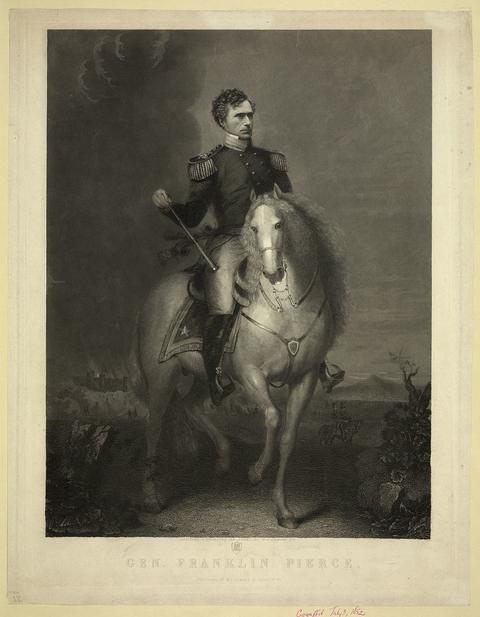

At the end of the Crimean War, in 1856, the European powers inked the Declaration of Paris, adopting the U.S.’s long-favored rule in favor of neutral commerce in wartime, but also purporting to outlaw the use of private vessels in wartime. Because the United States had relied heavily on such privateers in previous conflicts, President Franklin Pierce angrily refused to sign on.

Credit: Gen. Franklin Pierce, designed and engraved on steel by W.L. Ormsby, N.Y., Library of Congress.

-

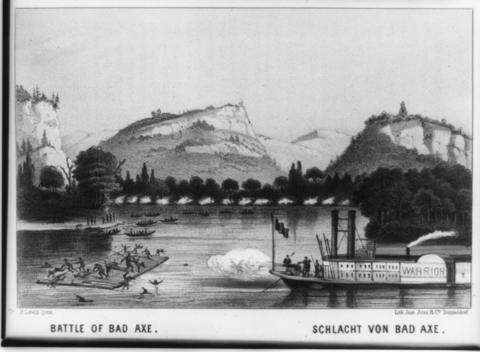

When he became president, Abraham Lincoln’s only experience of war was a brief stint in the 1832 Black Hawk War, a short but ugly conflict that ended at the Battle of Bad Axe in a terrible slaughter of Chief Black Hawk’s band of men, women, and children as they tried to escape the Illinois militia and get back to the west bank of the Mississippi.

Credit: Battle of Bad Axe (Schlacht von Bad Axe), by H. Lewis pinx.; Lith. Inst. Arnz & Co., Dusseldorf.

-

![<p>The first week of the war presented President Abraham Lincoln, shown here in May 1861, with a crisis in the laws of war at sea; controversy dogged his decision to blockade the South and treat Confederate privateers as pirates.</p><p>Credit: Matthew Brady, <em>[Abraham Lincoln, seated next to small table, in a reflective pose, May 16, 1861]</em>, 1861. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Abraham Lincoln](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/14_lincoln_3b32191u.jpg?itok=AkEECLK0)

The first week of the war presented President Abraham Lincoln, shown here in May 1861, with a crisis in the laws of war at sea; controversy dogged his decision to blockade the South and treat Confederate privateers as pirates.

Credit: Matthew Brady, [Abraham Lincoln, seated next to small table, in a reflective pose, May 16, 1861], 1861. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>Secretary of State William Seward used social occasions with the European diplomatic corps to craft the Lincoln administration’s distinctively pragmatic approach to the laws of war.</p><p>Credit: William J. Baker, <em>[The Secretary of State and the diplomatic corps at Trenton Falls, New York]</em>, 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> William Seward](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/15_seward_23732u.jpg?itok=F8YlRBz8)

Secretary of State William Seward used social occasions with the European diplomatic corps to craft the Lincoln administration’s distinctively pragmatic approach to the laws of war.

Credit: William J. Baker, [The Secretary of State and the diplomatic corps at Trenton Falls, New York], 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>The Union blockade of southern ports was notoriously porous, but its basis in the laws of war accomplished the crucial goal of placating the European powers and holding off intervention in the war. Alfred Waud’s sketch for Harper’s Weekly captured the life of the blockade that Lincoln, Seward, and Secretary of War Gideon Welles constructed.</p><p>Credit: Alfred R. Waud, <em>[Incident in the blockade]</em>, c. 1860-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Union Blockade](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/16_waud_blockade_21460u.jpg?itok=PdHj8vBv)

The Union blockade of southern ports was notoriously porous, but its basis in the laws of war accomplished the crucial goal of placating the European powers and holding off intervention in the war. Alfred Waud’s sketch for Harper’s Weekly captured the life of the blockade that Lincoln, Seward, and Secretary of War Gideon Welles constructed.

Credit: Alfred R. Waud, [Incident in the blockade], c. 1860-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

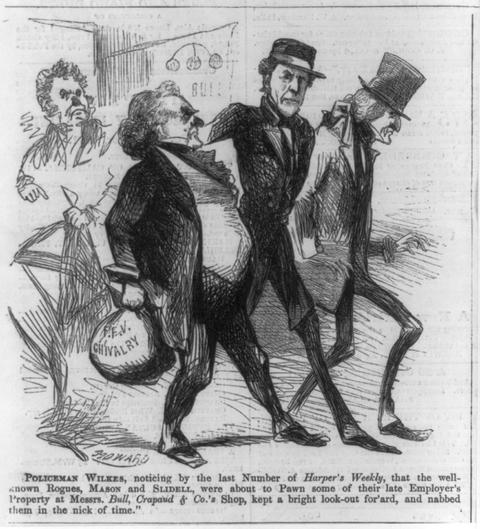

Captain Charles Wilkes seized Confederate diplomats Mason and Slidell from a British vessel in November 1861. This early controversy over neutral and belligerent rights at sea nearly brought Britain (depicted as the angry John Bull in the rear) to war against the Union.

Credit: “Policeman Wilkes,” from Harper’s Weekly, November 30, 1861. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

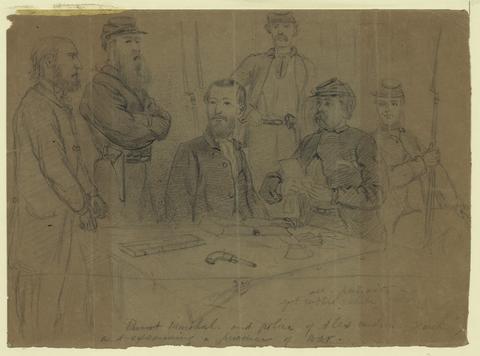

In July 1861, when Alfred Waud captured this scene of an early prisoner of war being interviewed by Union soldiers and a local law enforcement officer for Harper’s Weekly, it was not yet clear whether Confederate soldiers would be treated as prisoners of war or as traitors and criminals.

Credit: Alfred R. Waud, Provost Marshal--and police of Alexandria searching and examining a prisoner of war, 1861. Morgan Collection of Civil War drawings, Library of Congress.

-

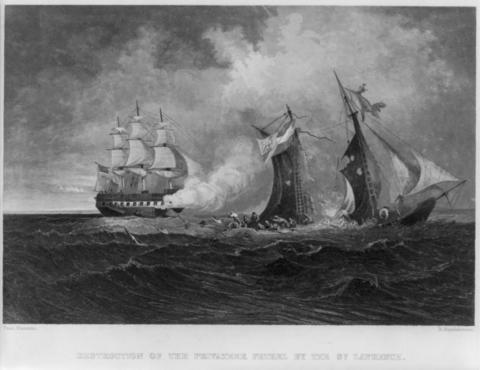

Southerners serving on private vessels – so-called privateers – were initially prosecuted as pirates. But treating Confederates as soldiers on the battlefield made it politically impossible to treat them as pirates at sea. Here the Union Navy sinks the Confederate privateer Petrel outside of Charleston in July 1861.

Credit: Destruction of the privateer Petrel by the St. Lawrence, 1862. Steel engraving by Robert Hinshelwood, after painting by Paul Manzoni. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

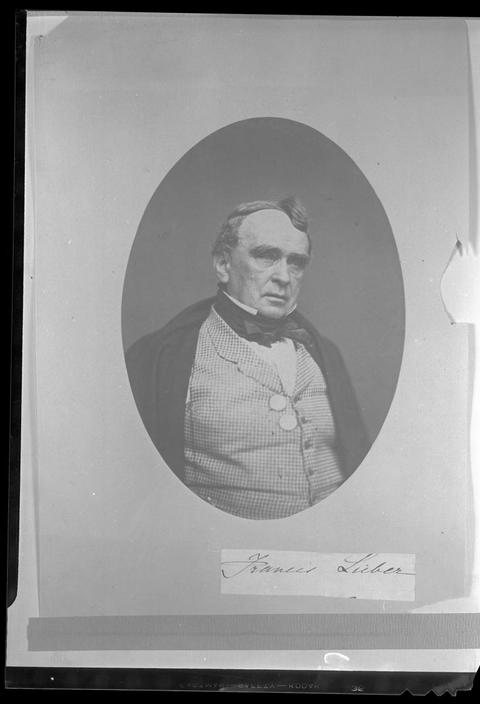

In the first year of the war, Francis Lieber tought the laws of war at Columbia College after living in South Carolina for two decades.

Credit: Francis Lieber, c. 1859. Courtesy of the University Archives, Columbia University in the City of New York.

-

![<p>Lincoln promoted the bookish Henry Halleck to General-in-Chief and called him to Washington, bringing an expert on the laws of war into the Union high command in the fall of 1862.</p><p>Credit: John A. Scholten, <em>[Portrait of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, officer of the Federal Army]</em>, c. 1860-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Henry Halleck](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/22_halleck_06956u.jpg?itok=I1ihqixX)

Lincoln promoted the bookish Henry Halleck to General-in-Chief and called him to Washington, bringing an expert on the laws of war into the Union high command in the fall of 1862.

Credit: John A. Scholten, [Portrait of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, officer of the Federal Army], c. 1860-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

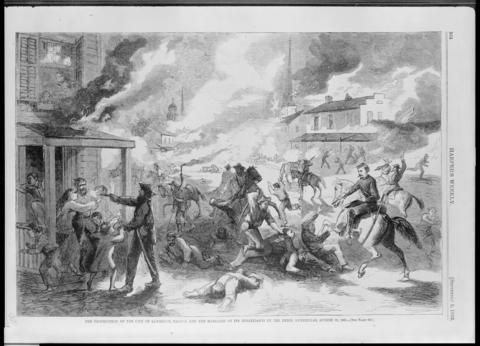

Guerrillas such as the infamous Bloody Bill Quantrill harassed Union-sympathizers in Missouri from 1861 onward. Here Harpers’ Weekly depicts Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence, Kansas in 1863.

Credit: The destruction of the city of Lawrence, Kansas, and the massacre of its inhabitants by the Rebel guerrillas, August 21, 1863, from Harper’s Weekly, September 5, 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

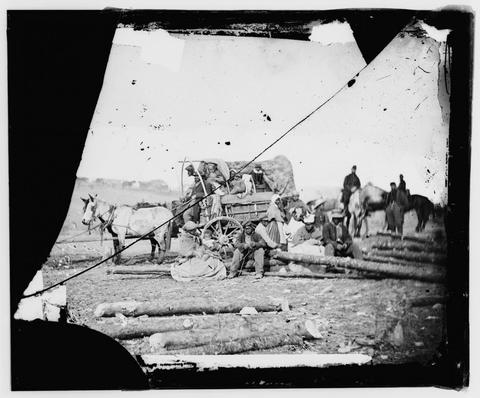

Fugitive slaves streaming into Union lines forced the issue of slavery onto the Union agenda.

Credit: David B. Woodbury, A Negro family coming into the Union Lines, 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

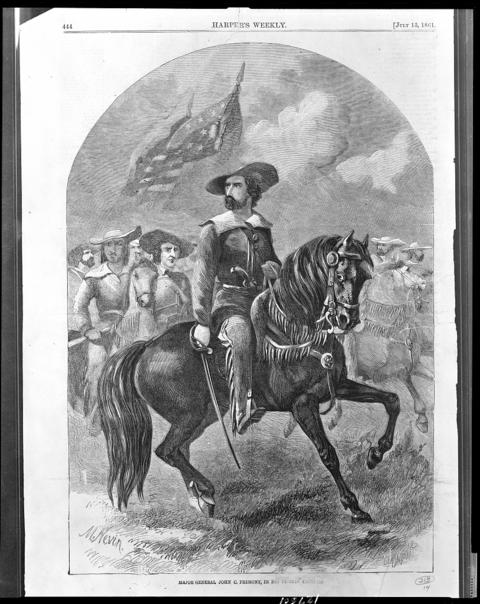

John Frémont’s ill-timed emancipation order forced Lincoln to address explicitly the relationship between slavery and the laws of war.

Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

-

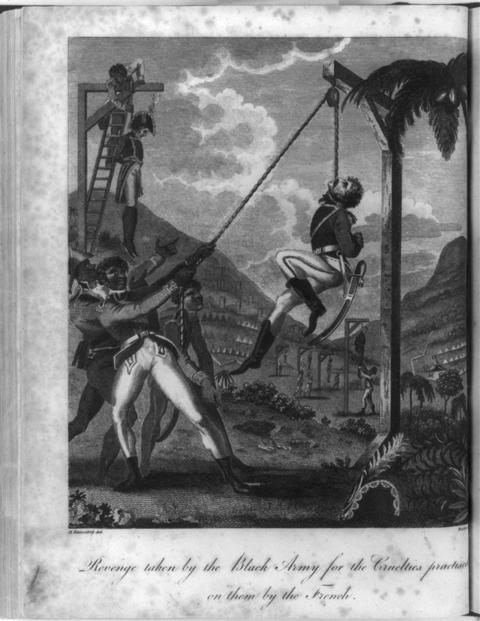

The long history of slave rebellions such as the one in Haiti in 1791 led to widespread concern among whites North and South that freeing the slaves would produce indiscriminate bloodshed and terrible atrocities.

Credit: Revenge taken by the Black Army, 1805. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

Major-General George McClellan bitterly opposed Emancipation a war tactic unfit for a civilized nation. But McClellan’s limited war strategy stalled on the Virginia Peninsula in the spring and early summer of 1862. Artist Alfred Waud’s sketch of McClellan’s headquarters during religious services on a Sunday in July 1862 captured the Union commander’s notion of Christian warfare.

Credit: Alfred R. Waude, Sunday at McClellans headquarters, Religious Services, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>By the fall of 1862, when Lincoln travelled to the battlefield at Antietam in Maryland, he had decided on Emancipation. Pictured here with McClellan, who bitterly opposed freeing slaves as a dangerous and uncivilized step in warfare.</p><p>Credit: Alexander Gardner, <em>[Abraham Lincoln on battlefield at Antietam, Maryland]</em>, 1862. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Abraham Lincoln on battlefield at Antietam](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/28_lincoln_antietam_3a05990u.jpg?itok=KnjdJjJc)

By the fall of 1862, when Lincoln travelled to the battlefield at Antietam in Maryland, he had decided on Emancipation. Pictured here with McClellan, who bitterly opposed freeing slaves as a dangerous and uncivilized step in warfare.

Credit: Alexander Gardner, [Abraham Lincoln on battlefield at Antietam, Maryland], 1862. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

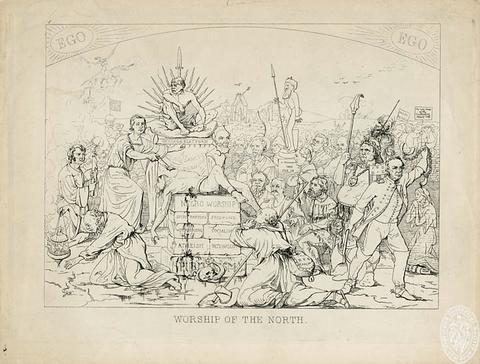

Adalbert Volck’s 1862-63 cartoon depicted leading Union men as infidels justifying Emancipation by the terrible motto inscribed on the altar of Negro Worship: “The End Sanctifies the Means.”

Credit: Adalbert John Volck, Worship of the North, c. 1861-1863. Maryland Historical Society..

-

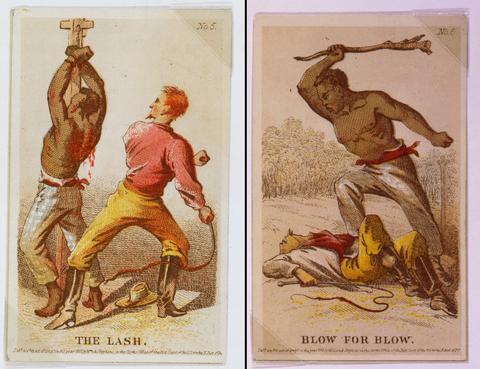

With the decision not only to emancipate the slaves behind Confederate lines but to enlist them and other blacks into the Union Army, it seemed that the Civil War had turned the violence of slavery upside down.

Credit: Left: Henry Louis Stephens, The Lash, c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Right: Henry Louis Stephens, Blow for Blow, c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

By late 1862, when he began work on a code for the laws of war, Francis Lieber had lost one son killed fighting for the Confederacy and seen a second gravely injured while fighting for the Union. The costs of the war were etched on his face in this grave portrait for the Columbia College 1862 class book.

Credit: Francis Lieber, Class of 1862 class photograph, 1862. Courtesy of the University Archives, Columbia University in the City of New York.

-

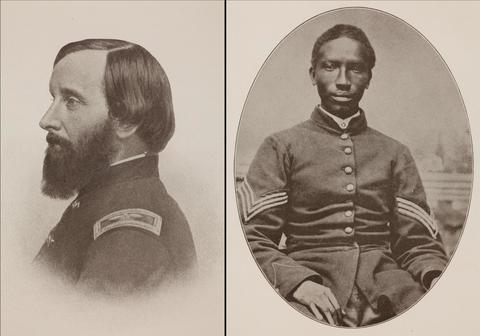

Thomas Wentworth Higginson and First Sergeant Henry Williams led raids by the Union’s First South Carolina Volunteers to bring away slaves in the backcountry. Lieber’s code aimed to legitimate Emancipation and the arming of black soldiers.

Credit: Thomas Wentworth Higginson and First Sergeant Henry Williams, from Marry Thacher Higginson, Letters and Journals of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1846-1906 (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1921). Courtesy of the Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

-

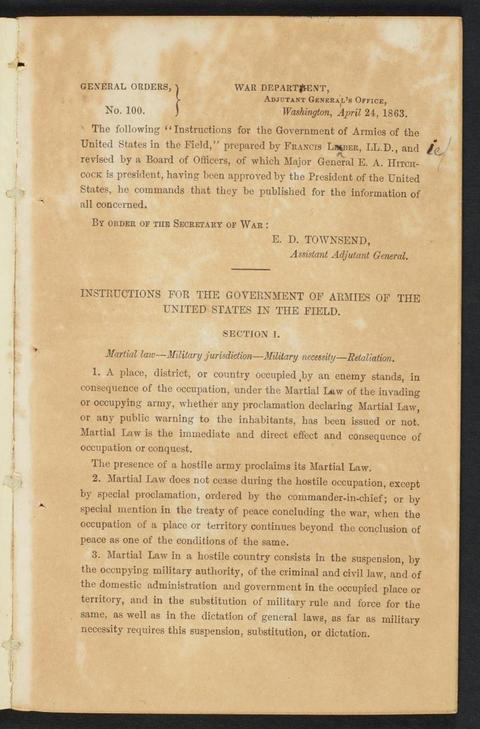

The first page of the original General Orders No. 100, which Lieber drafted and Lincoln issued in the spring of 1863. The handwritten correction is probably in Lieber’s own hand.

Credit: General Orders No. 100, 1863. Courtesy of the Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University.

-

![<p>By the end of the war, nearly two hundred thousand black men served in the Union armed forces.</p><p>Credit: Samuel A. Cooley, <em>[Beaufort, South Carolina. 29th Regiment from Connecticut]</em>, 1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> 29th Regiment from Connecticut](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/34_29th_conn_03373a.jpg?itok=bmbMQZwL)

By the end of the war, nearly two hundred thousand black men served in the Union armed forces.

Credit: Samuel A. Cooley, [Beaufort, South Carolina. 29th Regiment from Connecticut], 1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>Despite fears that the former slaves would fight with savage ferocity, most black regiments performed heroically and honorably, often despite grave provocations.</p><p>Credit: Left: Henry Louis Stephens, <em>Make Way for Liberty!</em>, c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Right: Alfred R. Waude, <em>[Black Soldier]</em>, c. 1862-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Black Soldiers](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/image35.jpg?itok=OtsTmGZd)

Despite fears that the former slaves would fight with savage ferocity, most black regiments performed heroically and honorably, often despite grave provocations.

Credit: Left: Henry Louis Stephens, Make Way for Liberty!, c. 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Right: Alfred R. Waude, [Black Soldier], c. 1862-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>William Tecumseh Sherman’s hard form of war put into action the Union’s uncompromising 1863 instructions for the laws of war. Pictured here outside Atlanta in 1864.</p><p>Credit: George N. Barnard,<em> [Atlanta, Ga. Gen. William T. Sherman on horseback at Federal Fort No. 7]</em>, 1864. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.</p> William Tecumseh Sherman](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/36_sherman_horseback_03379a.jpg?itok=FG47lWvD)

William Tecumseh Sherman’s hard form of war put into action the Union’s uncompromising 1863 instructions for the laws of war. Pictured here outside Atlanta in 1864.

Credit: George N. Barnard, [Atlanta, Ga. Gen. William T. Sherman on horseback at Federal Fort No. 7], 1864. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.

-

![<p>Sherman defended his shelling of Atlanta by arguing that short and sharp wars were more humane in the long run than the tepid conflicts imagined by the jurists of the eighteenth century. The shell-damaged Ponder House in Atlanta bore the effects of Sherman’s barrage.</p><p>Credit: George N. Barnard,<em> [Atlanta, Ga. The shell-damaged Ponder House]</em>, 1864. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.</p> The shell-damaged Ponder House in Atlanta](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/37_ponder_house_02230a.jpg?itok=jjLYjdgg)

Sherman defended his shelling of Atlanta by arguing that short and sharp wars were more humane in the long run than the tepid conflicts imagined by the jurists of the eighteenth century. The shell-damaged Ponder House in Atlanta bore the effects of Sherman’s barrage.

Credit: George N. Barnard, [Atlanta, Ga. The shell-damaged Ponder House], 1864. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.

-

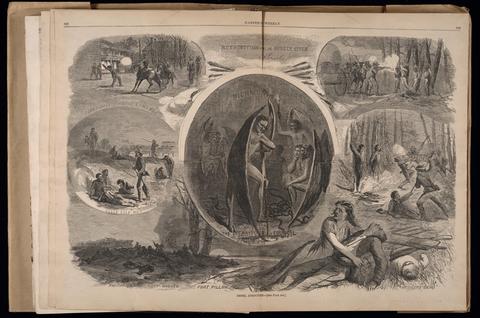

The northern press depicted Confederate soldiers shooting captured black teamsters from the Union Army in May 1864.

Credit: Rebel Atrocities, in Harper’s Weekly, May 21, 1864. Courtesy of the General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

-

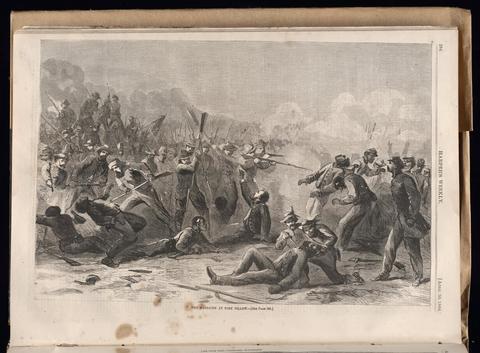

Harper’s Weekly portrayed the grisly massacre of black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow for readers all over the North.

Credit: Massacre at Fort Pillow, in Harper’s Weekly, April 30, 1864. Courtesy of the General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

-

![<p>Nathan B. Forrest commanded Confederate troops at Fort Pillow, the site of the most notorious (but not the only) massacre of black Union soldiers.</p><p>Credit: <em>[General Nathan B. Forrest]</em>, c. 1861-1865. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.</p> General Nathan B. Forrest](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/40_nathan_bedford_forrest_00082u.jpg?itok=PDL2R-9c)

Nathan B. Forrest commanded Confederate troops at Fort Pillow, the site of the most notorious (but not the only) massacre of black Union soldiers.

Credit: [General Nathan B. Forrest], c. 1861-1865. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

-

![<p>Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the grandson of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, used the Union’s law of war code to insist that captured black Union soldiers be treated as prisoners of war regardless of race.</p><p>Credit: Matthew B. Brady, <em>[Ethan Allen Hitchcock, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front]</em>, c. 1853-1859. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Ethan Allen Hitchcock](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/41_ethan_allen_hitchcock_3d01971u.jpg?itok=tS6H1ZTC)

Ethan Allen Hitchcock, the grandson of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, used the Union’s law of war code to insist that captured black Union soldiers be treated as prisoners of war regardless of race.

Credit: Matthew B. Brady, [Ethan Allen Hitchcock, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing front], c. 1853-1859. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>The code’s insistence on equal treatment of black soldiers helped bring an end to prisoner exchanges and contributed to the humanitarian toll in the war’s prison camps. Images of emaciated Union prisoners made their way to the public in 1864.</p><p>Credit: <em>[A Federal prisoner, returned from prison, full-length, seated, nude, facing front]</em>, c. 1861-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> A Federal prisoner, returned from prison](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/42_federal_prisoner_3g07966u.jpg?itok=Ay8PR3x7)

The code’s insistence on equal treatment of black soldiers helped bring an end to prisoner exchanges and contributed to the humanitarian toll in the war’s prison camps. Images of emaciated Union prisoners made their way to the public in 1864.

Credit: [A Federal prisoner, returned from prison, full-length, seated, nude, facing front], c. 1861-1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

Union camps for Southern prisoners swelled with new detainees after the end of prisoner exchanges. Though less notorious than Southern camps, they were nearly as deadly as their Confederate counterparts. Confederate soldiers here await transportation to a Union camp.

Credit: Confederate prisoners at Belle Plain Landing, Va., captured with Johnson's Division, May 12, 1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

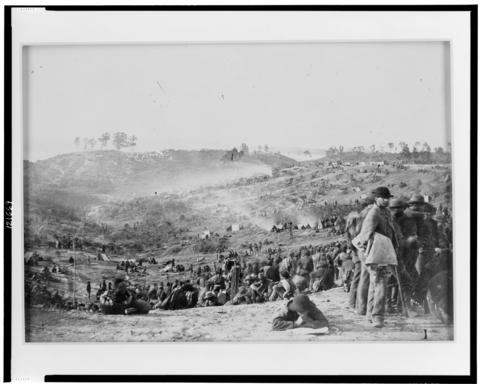

The terribly overcrowded Confederate camp at Andersonville, Georgia was the war’s most notorious prisoner of war camp, though not its deadliest. Here captured Union soldiers draw their rations.

Credit: Drawing rations; view from main gate. Andersonville Prison, Georgia, August 17, 1864. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 162, 165-A-445.

-

![<p>At the end of July 1863, just days before he sat for this photograph, Lincoln issued an order drawing expressly on the code and promising to retaliate against Southern soldiers for the execution or enslavement of black Union soldiers or their white officers.</p><p>Credit: Alexander Gardner, <em>[Abraham Lincoln, full-length portrait, seated, facing slightly right]</em>, 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> [Abraham Lincoln, full-length portrait](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/45_lincoln_july_1863.jpg?itok=sxmFKKXv)

At the end of July 1863, just days before he sat for this photograph, Lincoln issued an order drawing expressly on the code and promising to retaliate against Southern soldiers for the execution or enslavement of black Union soldiers or their white officers.

Credit: Alexander Gardner, [Abraham Lincoln, full-length portrait, seated, facing slightly right], 1863. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

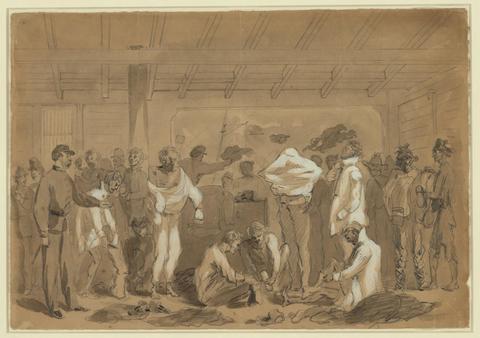

Prisoner exchanges finally resumed in the last weeks of the war; artist Alfred Waud sketched exchanged Union soldiers receiving new clothes in December 1864.

Credit: Alfred R. Waude, Returned prisoners of war exchanging their rags for new clothing on board Flag of Truce boat New York, 1864. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

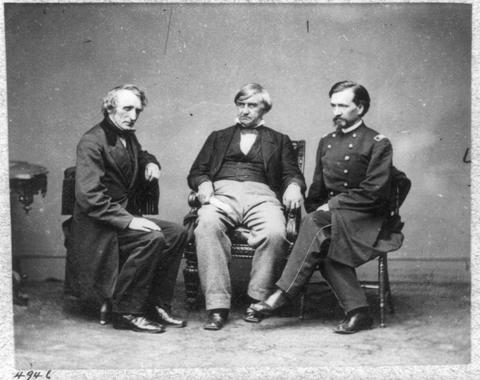

Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt (center) led a team of the best and brightest young lawyers of the Union. During the last two years of the war and in its immediate aftermath, judge advocates like John Bingham (left) and Henry Burnett (right) prosecuted nearly a thousand Confederates and southern sympathizers for violations of the laws of war.

Credit: Brvt. Maj. General Joseph Holt and Group, Civil War Photograph Collection, Library of Congress.

-

Ohio politician and Southern sympathizer Clement Vallandigham offered an early test case in the Lincoln administration’s strategy of using the laws of war to circumvent Congress, the courts, and the writ of habeas corpus.

Credit: Hon. Clement Laird Vallandigham of Ohio, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

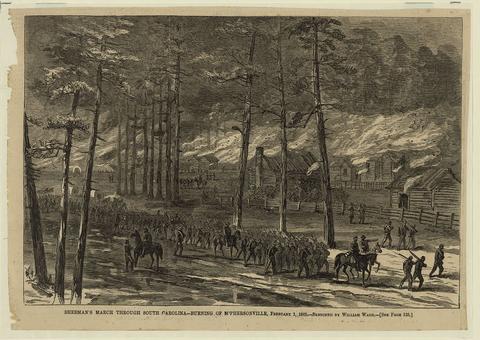

Sherman’s march to the sea showed how decentralized modern armies could wreak havoc for civilians. The Union code authorized most of the destruction Sherman himself ordered, but the law was incapable of constraining the unauthorized violence that the march unleashed.

Credit: William Waude, Sherman's March Through South Carolina - Burning of McPhersonville, February 1, 1865, from Harper’s Weekly, March 4, 1865, courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>When Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met at Appomattox in April 1865, they rehearsed the formal structure of the laws of war: they met as equals in the eyes of the law, even though Grant’s army was far stronger and even though Grant believed his cause to be just and Lee’s cause to be unjustifiable.</p><p>Credit: Alfred R. Waude, <em>[Robert E. Lee leaving the McLean House following his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant]</em>, Library of Congress.</p> Robert E. Lee leaving the McLean House following his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/50_appomattox.jpg?itok=Jvvx011i)

When Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met at Appomattox in April 1865, they rehearsed the formal structure of the laws of war: they met as equals in the eyes of the law, even though Grant’s army was far stronger and even though Grant believed his cause to be just and Lee’s cause to be unjustifiable.

Credit: Alfred R. Waude, [Robert E. Lee leaving the McLean House following his surrender to Ulysses S. Grant], Library of Congress.

-

![<p>In April 1865, the capture of Jeff Davis in women’s clothing and the arrest of the conspirators accused of assassinating President Lincoln produced widespread expectations that a wave of executions would follow.</p><p>Credit: <em>[Uncle Sam’s Menagerie]</em>, 1865, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Uncle Sam’s Menagerie](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/51_jeff_davis_april_1865.jpg?itok=GrslX0lg)

In April 1865, the capture of Jeff Davis in women’s clothing and the arrest of the conspirators accused of assassinating President Lincoln produced widespread expectations that a wave of executions would follow.

Credit: [Uncle Sam’s Menagerie], 1865, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>The hooded bodies of three men and one woman convicted and sentenced to death by a military commission for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Lincoln.</p><p>Credit: Alexander Gardner, <em>[Washington, D.C. Hanging hooded bodies of the four conspirators; crowd departing]</em>, 1865. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.</p> Hanging hooded bodies of the four conspirators](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/52_hanging_hooded_04230a.jpg?itok=tbTuFXvW)

The hooded bodies of three men and one woman convicted and sentenced to death by a military commission for conspiring with John Wilkes Booth to assassinate Lincoln.

Credit: Alexander Gardner, [Washington, D.C. Hanging hooded bodies of the four conspirators; crowd departing], 1865. Selected Civil War photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress.

-

![<p>Champ Ferguson, one of the most feared southern guerrillas of the war, was tried and executed for war crimes that included systematically executing black soldiers.</p><p>Credit: <em>[Photo of Champ Ferguson, rebel guerrilla, during his trial, with a guard of the 9th Michigan Infantry]</em>, 1865. Louis E. Springsteen Photograph Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.</p> Photo of Champ Ferguson, rebel guerrilla, during his trial](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/53_champ_ferguson_hs1495at600.tif_.jpg?itok=MnHanE8Z)

Champ Ferguson, one of the most feared southern guerrillas of the war, was tried and executed for war crimes that included systematically executing black soldiers.

Credit: [Photo of Champ Ferguson, rebel guerrilla, during his trial, with a guard of the 9th Michigan Infantry], 1865. Louis E. Springsteen Photograph Collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

-

![<p>Captain Henry Wirz, the commander at Andersonville Prison, was executed for violations of the laws of war. He was one of nearly a thousand Confederate soldiers or sympathizers to face law of war charges in front of Union military commissions.</p><p>Credit: Alexander Gardner, <em>[Washington, D.C. Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold]</em>, 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.</p> Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/54_wirz_04194a.jpg?itok=YbLuPzni)

Captain Henry Wirz, the commander at Andersonville Prison, was executed for violations of the laws of war. He was one of nearly a thousand Confederate soldiers or sympathizers to face law of war charges in front of Union military commissions.

Credit: Alexander Gardner, [Washington, D.C. Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold], 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

The arrest and military commission conviction of Lambdin Milligan for crimes arising out of his membership in a pro-Southern secret military organization in Indiana led the Supreme Court to reign in the efforts of Halleck, Holt, and Lieber to use the laws of war. In the process, the Court substantially hindered the Union military’s efforts to protect the freedom of four million freedpeople around the South.

Credit: Image from Samuel Klaus, The Milligan Case (New York: Knopf, 1928), courtesy of Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

-

Congressman John Bingham had put the laws of war to use as a judge advocate under Joseph Holt during the war. In 1866 and 1867 he aimed to restore constitutional normalcy and move away from the laws of war. Bingham drafted the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment as an alternative (and much narrower) source of Union authority in the South.

Credit: The Library of Congress.

-

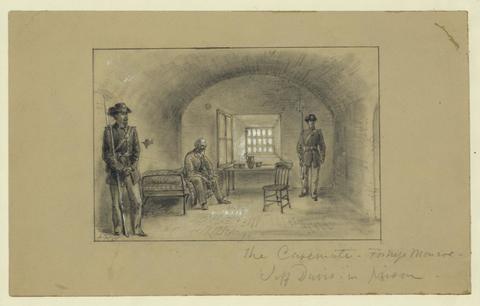

Artist Alfred Waud sketched Jefferson Davis confined at Fort Monroe in 1865.

Credit: Alfred R. Waude, The casemate, Fortress Monroe, Jeff Davis in prison, 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

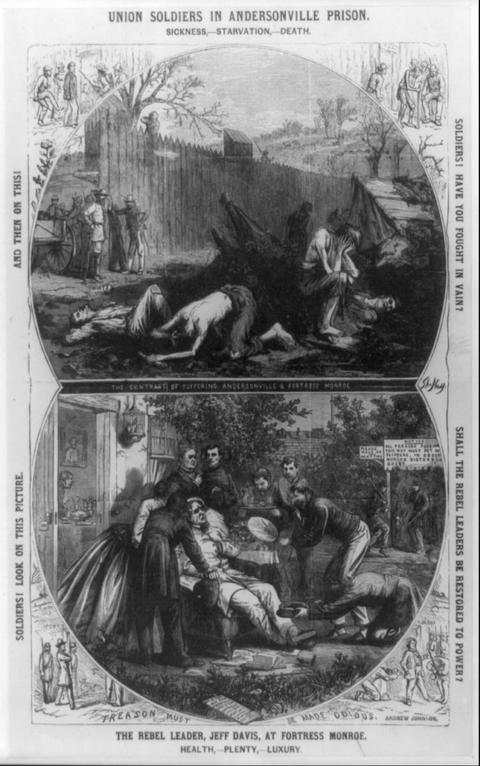

The capture of Jefferson Davis in the spring of 1865 touched off two years of debate over his fate; Northern publications like Harper’s Weekly pointedly observed the contrast between the conditions of Davis’s confinement and those of Union prisoners of war. Davis’s release in 1867 and pardon in 1868 showed just how difficult it would be to treat southerners as criminals and traitors after four years of treating them as soldiers.

Credit: Thomas Nast, Union soldiers in Andersonville prison / The rebel leader, Jeff Davis, at Fortress Monroe, 1865. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

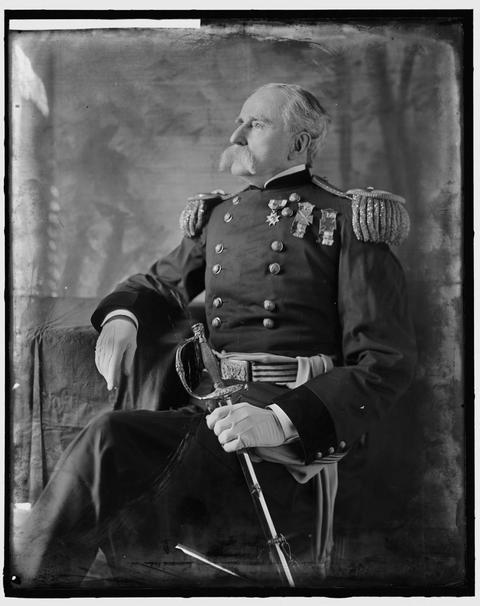

Francis Lieber’s son G. Norman Lieber served as Judge Advocate General for nearly two decades until 1901. He brought the code his father drafted to Indian wars in the west and to the brutal war in the Philippines.

Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer, General G. Norman Lieber, c. 1905. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

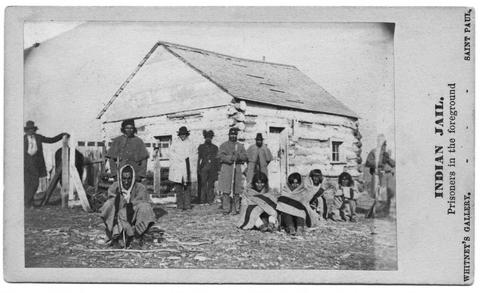

The log house behind the Dakota-Sioux Indian prisoners in the foreground was the site the military commission trials of 392 Sioux, 303 of whom were sentenced to death. Photograph taken in 1862.

Credit: Adrian J. Ebell, Indian jail for Sioux uprising captives, 1862. Minnesota Historical Society.

-

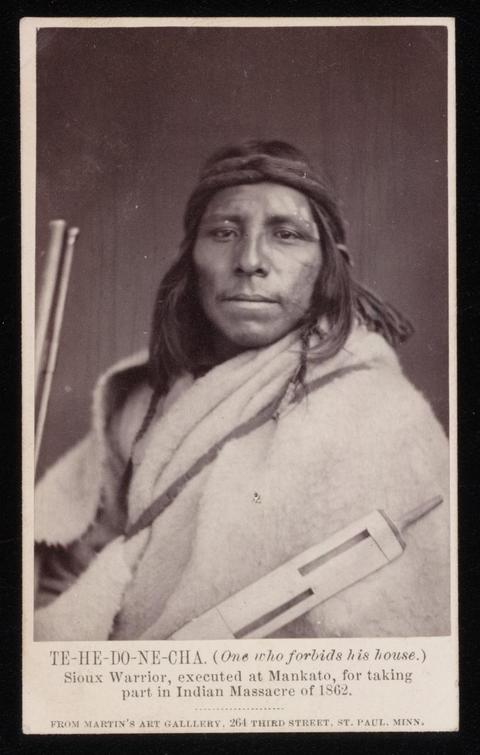

Lincoln reviewed the sentences of all 303 Dakota-Sioux warriors sentenced to death by military commissions in Minnesota; he approved the execution of thirty-nine of them, including the man pictured here, on the ground that they had participated in indiscriminate warfare against noncombatants.

Credit: Te-he-do-ne-cha. (One who forbids his house.) Sioux warrior, executed at Mankato, for taking part in Indian Massacre of 1862, c. 1857-1863. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

-

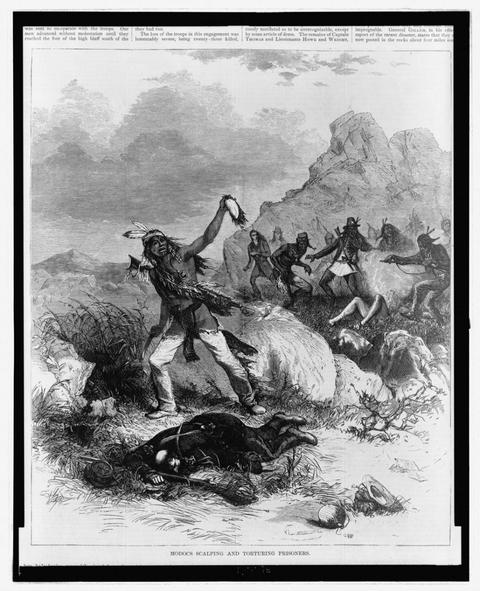

A nasty conflict between the U.S. Army and a band of Modoc Indians in Oregon in 1873 reprised the scalping scenes of the pre-Civil War era.

Credit: Modocs scalping and torturing prisoners, from Harper’s Weekly, 1873. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

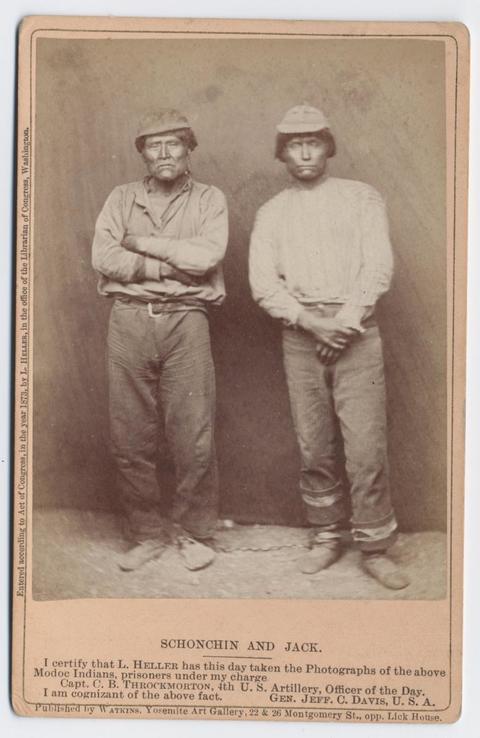

Captain Jack, standing at right, led the Modocs before being executed for killing the U.S. officer under a flag of truce. Men like Andrew Jackson had simply executed the Indians they captured before the Civil War, but now captured Indian warriors like Jack were tried by military commission.

Credit: Lewis Herman Heller & Carleton E. Watkins, Schonchin and Jack, 1873. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

-

President Grover Cleveland proposed to execute them, but Geronimo and his band of Chiricahua Apache – men, women, and children alike -- were taken by train from their native southwest into more than two decades as prisoners of war.

Credit: Chiricahua Prisoners, including Geronimo, 1886. National Archives and Records Administration, 111-SC-82320.

-

Henri Dunant, a failed Swiss banker and entrepreneur, became the inspiration for the International Committee of the Red Cross and the first Geneva Convention of 1864 after witnessing the suffering of the wounded on a battlefield in northern Italy in 1859.

Credit: Library of Congress.

-

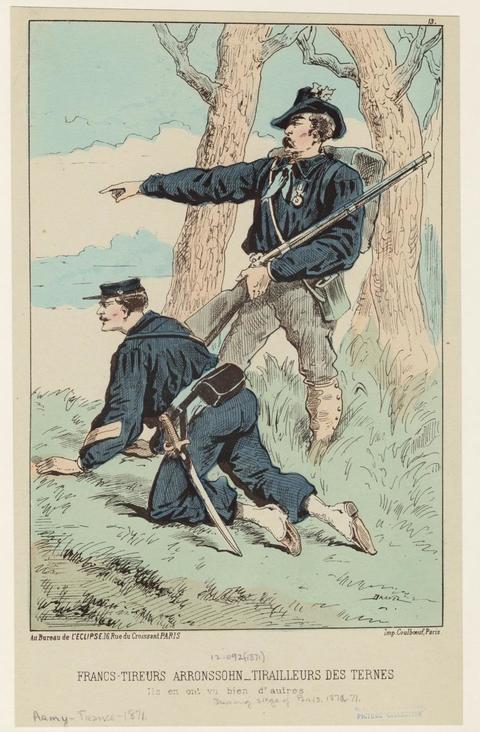

After the Civil War, the Union’s code of 1863 spread around the world. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 saw the code applied to irregular fighters such as the so-called Franc-tireurs who resisted Prussian occupation.

Credit: Francs-tireurs Arronssohn, tirailleurs des ternes : ils en ont vu bien d'autres, from Souvenirs du siége de Paris : les défenseurs de la capitale. (Paris : Bureau de l' Eclipse, 1871). Mid-Manhattan Library, Picture Collection, New York Public Library.

-

The Prussian jurist Johann Caspar Bluntschli translated the code into German and spread its influence in Europe.

Credit: Johann Caspar Bluntschli, from Zürich: Geschichte, Kultur, Wirtschaft (Zürich: Gebr. Fretz, 1933), courtesy Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

-

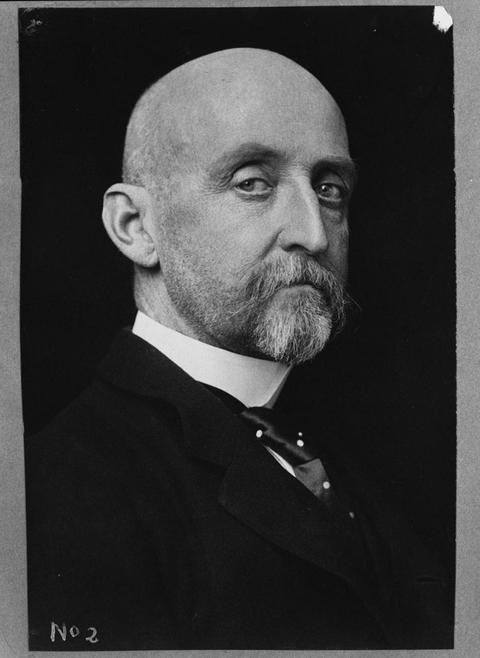

Channeling the spirit of the Civil War code of Lincoln and Lieber, the formidable Alfred Thayer Mahan dominated the U.S. delegation to the conference that modernized the laws of war in 1899.

Credit: Alfred Thayer Mahan, c. 1900. LC-USZ62-3124, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

-

![<p>U.S. armed forces in the Philippines engaged in the widespread use of torture tactics such as the “water cure,” demonstrated here by a team of American soldiers.</p><p>Credit: <em>[Water Cure]</em>, 1899-1902. 111-SC-98202, National Archives and Records Administration.</p> Water Cure](https://documents.law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/styles/adaptive/adaptive-image/public/69_nara_photo_111-sc-98202.jpg?itok=J0LfxXPf)

U.S. armed forces in the Philippines engaged in the widespread use of torture tactics such as the “water cure,” demonstrated here by a team of American soldiers.

Credit: [Water Cure], 1899-1902. 111-SC-98202, National Archives and Records Administration.

-

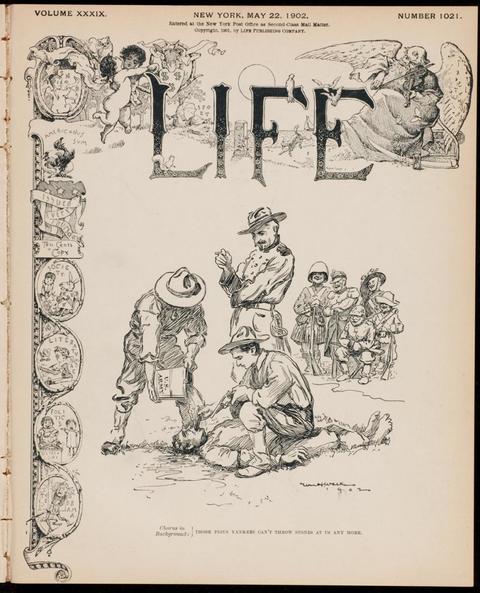

Life Magazine put the water cure on its cover in 1902 as reports of the widespread use of torture in the Philippines reached American readers.

Credit: The Water Cure, from Life Magazine, May 22, 1902. Courtesy of the Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University.

-

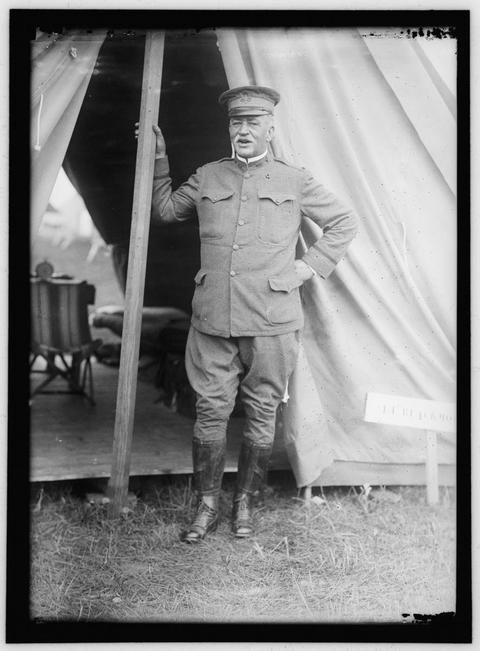

Colonel Edwin F. Glenn led a roving team of crack torture experts in the Philippines and was court martialed for violating the 1863 code’s prohibition on torture. Twelve years later he drafted the field manual on the laws of war that American officers would carry into two world wars.

Credit: Harris & Ewing, photographer, Plattsburg Reserve Officers Training Camp. Major Edwin F. Glenn, U.S.A., 1916. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.